Marla Hamburg Kennedy is another Manhattan gallerina with an impressive domestic showing space. Openings at her penthouse apartment-cum-gallery in Midtown, a few blocks south of Gavlak’s, are rambunctious social affairs, tables groaning with Middle Eastern treats, a yellow Labrador weaving hopefully through the throng in search of crumbs, and a crowd that includes skinny-jean-clad hipsters, glam girls in Grecian dresses and curator-types wearing geometric jewellery. The rooftop terrace has breathtaking views across the city, but if it rains, there’s ample space indoors for mingling and viewing. Yet there are no labels on the artwork that covers almost every wall and the only reminder that the evening has a commercial purpose is the tiny sign hanging next to the staircase, reading, almost apologetically: “Hamburg Kennedy Photography”.

The namesake gallerist is a charming host, an auburn-haired whirlwind who talks as if she’s worried she’ll run out of air at any moment. Synonymous with high-end photography in New York, she has several decades of experience in the art world, running commercial galleries and also museums, such as the MoMA offshoot PS1. Unlike Gavlak’s grand plan, Hamburg Kennedy’s home-showing space emerged as if by chance.

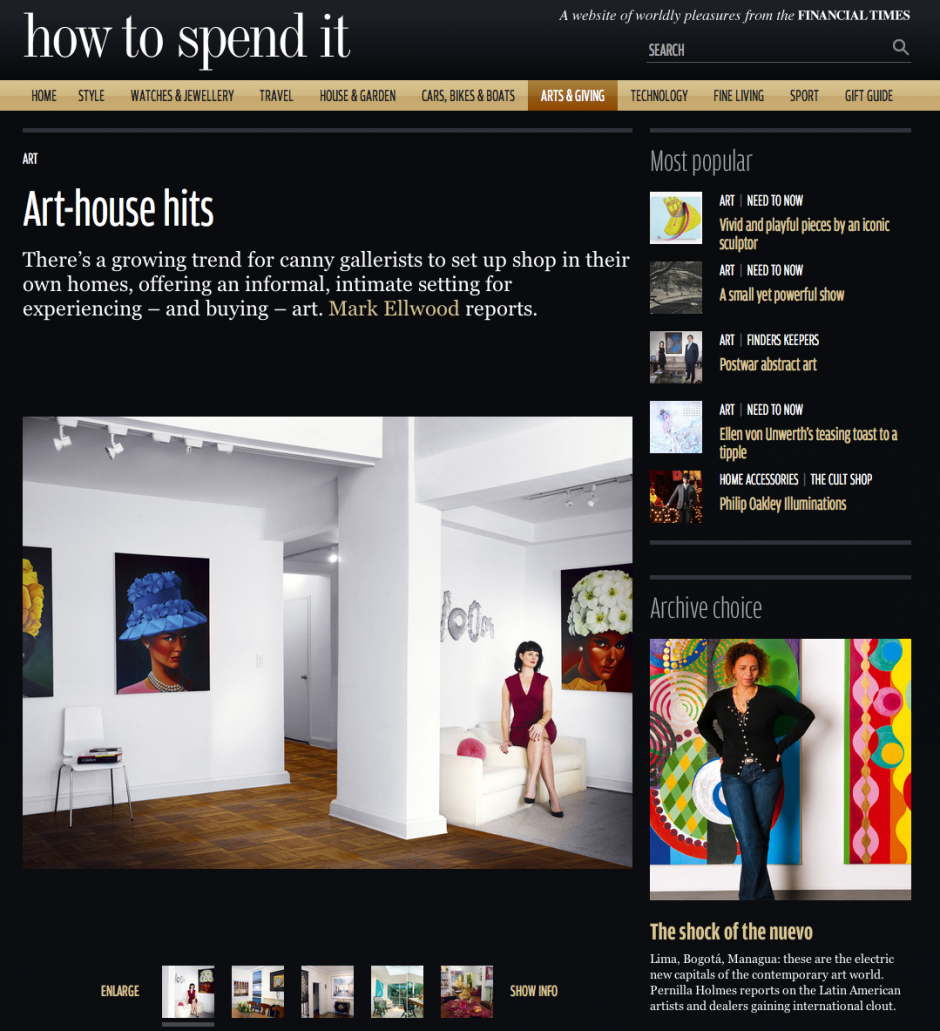

“This is a more intimate setting to meet clients, and it started casually – they would come every day, see my own collection, have lunch or drinks, and we’d discuss the art market or bring out books,” she explains. As clients began cherry-picking photos from her walls, Hamburg Kennedy moved her entire operation, including almost a dozen staff members, into her apartment; the walls now combine her own private collection and new for-sale works, although she’s flexible and will allow clients to buy almost any piece. “This is basically a private salon, where people come and go. And in New York, you can’t often combine living and working spaces like this.”

It’s an intentionally immersive experience for a client, one that underscores how personal the gallerist-collector relationship should be. “My collection reflects the aesthetic and the price point that I really believe is right now, and it’s a starting point for what they want to collect,” she adds, citing blue-chip pieces by German photographers Candida Höfer and Thomas Ruff as examples. “The domestic setting is extremely intimate and lends itself to developing a strong bond with your clients. You can’t really get that as much in a [traditional] gallery space. Most of my clients become family friends, which brings with it a level of trust and loyalty that is essential in being able to place art.”

Her biggest challenge has been working with children and animals around. Hamburg Kennedy’s stepson, who thrived amid the art-world chaos as a young child, absorbing it all quite naturally, is now a teenager and understandably sensitive. “We can’t have nudes – Thomas Ruff has a lot of explicit ones, and my stepson feels uncomfortable with them,” she notes. “And I run an extremely informal set-up, the opposite of a velvet-rope approach, with three cats and two dogs running round. I encourage people to bring animals, kids, whatever they want, when they visit. But as a consequence I have to employ a full-time housekeeper who’s constantly having to clean and tidy. It’s hard work when you live in a zoo.”